博文

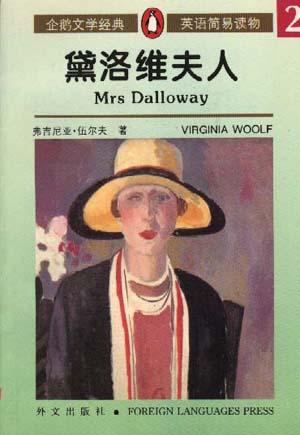

《黛洛维夫人》(MRS DALLOWAY)—企鹅简写版

||||

从头到尾读过的小说当中,下面的这本黛洛维夫人是最爱之一,虽然只是简写本,我却从这本书中感受到了英文的修辞之美,第一次读这本书到现在已经有好多年了,这当中,我经常在处于某种特定的情绪时翻翻这本小书。

前两天刚刚发现一款OCR识别的神器——ABBYY Finereader,所以花了两个小时的时间,将这本小书拍照、OCR、校正制作了完美的电子版,以后每次自己想看的时候就可以随时翻翻了。

MRS DALLOWAY

'I will buy the flowers,' said Mrs Dalloway; because Lucy was much too busy. Rumpelmayer's men were coming to take the doors off the sitting-room. And it was a wonderful morning, fresh and new, like a morning by the sea.

She remembered days like this at Bourton, when she opened the glass doors and moved like a swimmer into the soft fresh air of early morning. She was eighteen then. She remembered standing there looking at the flowers, at the trees with the birds flying around them, and thinking: some-thing terrible is going to happen. And Peter Walsh was amused to see her standing there so still and said at breakfast: 'Were you talking to the vegetables?' - or something like that. Peter Walsh will be back from India soon, she thought, some time in June or July. She could never remember any-thing from his letters, they were so uninteresting. It was his sayings that she remembered; his eyes, his pocket-knife, his smile, his unpleasantness sometimes, a few of his sayings.

She waited a moment in the street for a car to pass. A neighbour walking past thought: a lovely woman, so alive, quick and light as a bird, but grown very white since her illness. Having lived now for more than twenty years in Westminster, Mrs Dalloway knew so well that special silence before Big Ben sounds the hour. First the music, the warning. There! Out it came: one ... two ... three. She went on counting the numbers while she crossed Victoria Street. It's impossible to say why I love it all so much, she thought, but many people do: the noise, the movement, the cars and buses, the crowds, the music; the sound of an aeroplane high in the sky. It was life that she loved; and London; this moment in June. Because it was now June. The war was over — thank goodness it was over. The London season was beginning: sports matches; laughing girls who danced all night, then took their woolly dogs for a walk; rich old ladies out in their motor cars; shopkeepers putting out their best gold and silver pieces in the shop windows. And she, a part of it all, loving it all, was going to give her party that night.

But still the park, as she passed into it, was strangely silent: birds swimming slowly in the water, the sounds of the city far away. She thought again of Bourton, the times with Peter Walsh. Peter was impossible in many ways, always criticiz-ing; but he was just the person to walk with on a morning like this. She never wrote to him; but she often thought of him, calmly, without feeling angry. And a picture of him came back to her, here in St James's Park this beautiful morning, not that Peter ever noticed the trees and the grass and the children. He only put on his glasses if she told him to; and only then he looked. It was ideas that interested him: books, the world's problems, the things people did. He called her 'the perfect hostess'. She was born to be a perfect hostess, he said. And this made her cry alone in her bedroom, remembering his words.

So, she told herself, she was right to decide against marrying him; because married people needed sometimes to be free from each other, living together day after day in the same house; as she now lived with Richard. But Peter always wanted to be part of everything, to study everything, to know what her feelings were. It was too much. That evening years ago in the little garden, she had to break free from him, because their friendship was bad for them both, it was hurting each of them too much. For years after that she carried a deep sadness around with her. And now she remembered the terrible moment when she heard that Peter was married, to a woman he met on a boat, going to India! She could never forget that! He called her cold, unfeeling: she didn't under-stand how he felt. But really he was quite happy, he told her. He knew that his life was not successful but that didn't matter. The thought of this still made her angry.

Now she was at the exit from the park. She stood for a moment, looking at the buses in Piccadilly, feeling both very young and very old. She cut through everything like a knife; and at the same time stood outside life, just watching. She felt all alone, like someone far out at sea. Every day that she lived seemed dangerous. Of course she was not very clever, quite ordinary in fact. She knew almost nothing. She didn't often read a book. But she found every moment of life deeply interesting. She did not Want to say of Peter or of herself: 'I am this, I am that.' She remembered ... oh so many people, so many things. But everyone remembered; what she loved, was this, here, now, in front of her: that fat lady getting into a taxi. So does it matter, she asked herself, walking towards Bond Street, that one day I shall be dead and all this will go on without me? Will I not live on somehow, a part of the streets of London, of trees and houses, of people I have never met, like a thin sort of cloud?

She stopped to look at the books in a bookshop window. If only I had my life to live over again, she thought, crossing the street. But it's too late: no more marrying now, no having of children, just a woman walking in the crowd up Bond Street. Not Clarissa any more, just Mrs Dalloway.

Bond Street was wonderful early in the morning: shops with just one expensive hat or one tie; one shining fish sitting on its bed of ice. Passing shoeshops, dress shops, she remem-bered her daughter, Elizabeth. But Elizabeth wasn't interested in clothes. It was her dog Grizzle that she loved most. Well, better to love Grizzle than that unpleasant teacher Miss Kilman, who she spent so much time with. Miss Kilman was always badly dressed and always reading serious books, making you feel small. I can perhaps feel sorry for Miss Kilman, she thought, but I can't feel any love for her. Not in this world.

No. Forget her! she thought, pushing through the doors of Mulberry's the flower shop, where Miss Pym was waiting to welcome her. There were flowers everywhere: all the flowers of summer in great coloured bunches. And that fresh smell of gardens that she loved. She went from bunch to bunch, choosing, and the friendliness of Miss Pym drove the unpleasant thoughts away. Suddenly a noise like a gunshot came from the street. 'Oh those cars!' said Miss Pym, going to the window to look and coming back smiling, while Mrs Dalloway chose her flowers.

♦

In the sky above, an aeroplane was making letters. People outside Buckingham Palace or in Regent's Park or down by the river all looked up at the sky to see what the letters said.

'What are they looking at?' said Clarissa Dalloway, when Lucy opened the front door. Inside the house the air was cold, like the inside of a church. As the .door closed behind her, the outside world was shut away, bringing instead the comfort-able sounds and ways of home: the cook singing in the kitchen, a machine heard softly in another room. This too is my life, she thought, moving to the table at the entrance to read a message written there. Moments like these are flowers on the tree of life; moments that I must repay in kindness to the people who work for me, to dogs and birds, and especially to Richard my husband, who makes it all possible — the pleasant sounds, the soft green lights, the cook singing her Irish song. I must pay back something from these lovely saved moments, she thought, as she read the message, while Lucy stood beside her trying to explain:

' "Lady Bruton would like to know if Mr Dalloway will have lunch with her today."'

'Mr Dalloway, ma'am, asked me to tell you that he will not be at home for lunch.'

'Oh dear!' said Clarissa, and she and Lucy both felt a touch of sadness as Lucy took her umbrella and put it away. How hurtful that Lady Bruton asks Richard to lunch but not me, she thought. She began to go slowly upstairs, feeling herself old and alone, stopping for a moment at the stair window,

which let in the flowering of the day, and thinking: she did not ask me.

She passed the bathroom and came to the bedroom. She took off her hat and put it on the clean, white, narrow bed. In this small room she read late into the night, because she slept badly. Now since her illness Richard wanted her to rest in perfect quiet. And really she preferred it: since in her love for Richard something was now lost. She felt in herself a coldness; in some ways they were like strangers. The love that a man feels she felt only sometimes with other women. There was Sally Seton, for example. Wasn't it love that she felt for Sally Seton in the old days? Sally sitting on the floor, with her arms around her knees, smoking a cigarette. She could not take her eyes off Sally the first time they met. She was unusually beautiful, with those big dark eyes and that lovely voice, more like a foreigner than an English girl. That summer, when she first came to stay at Bourton, she walked in without a penny in her pocket one night after dinner. Aunt Helena was not pleased. But they sat up talking most of the night. Sally told her so many things she knew nothing about: sex, politics. It was all so exciting: she started reading books for hours at a time. Sally was so clever, so full of surprises: she cut the heads off flowers and put them swimming in dishes of water on the dinner table. One night she forgot her towel and ran from the bathroom to her bedroom without any clothes on. But the strange thing, looking back, was the clear, clean love she felt for Sally — not like the feeling for a man, a feeling that was only possible between women. She had a need to look after Sally, to save her from danger. Because in those days Sally did all sorts of wild things: she smoked cigars, rode her bicycle in the most dangerous places. She could remember standing in her bedroom at the top of the house and saying to herself: 'She is under this roof! She is under this roof!' The words meant nothing to her now. The old excitement could never come back. How Sally quite suddenly stopped'; picked a flower; kissed her on the lips. It was like a beautiful present to carry with you and keep but never look at. And she knew Peter was jealous, that he was against Sally, who was now busy asking someone to tell her the names of the stars.

But later, Peter helped her, taught her things: ideas and words which she still used every day. Why, when she thought of him, did she mostly remember their quarrels? What will he think of me now, she asked herself, when he comes back? Do I look older? Will he say that I look older? But it was true: since her illness her hair was now almost white. She crossed to the dressing-table and took off her rings. I am not old yet. I have just begun my fifty-second year, she thought. Months and months of it are still untouched. And she stood very still for a moment, looking at the glass, the dressing-table with its little bottles, seeing the thin pink face of the woman who that night was to give a party; Clarissa Dalloway; herself. These different parts made up one face, a thousand feelings made this one woman, who people in trouble turned to, while she kept some sides of herself hidden: the jealousies, the selfishness; Lady Bruton not asking her to lunch! Now, where was her dress?

Her evening dresses were in the cupboard. Clarissa carefully took out the soft green dress and carried it to the window. It needed mending. Not long ago, someone at a party put their foot on the skirt. In electric light the green shone but it lost its colour here in the sun. She must mend it. Lucy and the others had too much to do. This was the dress for her party tonight. She- picked up her sewing things and went downstairs to the sitting-room. As she went, she heard the sounds of people busy: voices, someone knocking, the noise of metal. Clean silver for the party. Everything was for the party!

'Oh Lucy,' she said, 'the silver does look nice!' And Lucy, at the sitting-room door, was asking to help mend her dress.

'No, no. You have enough to do. But thank you, Lucy, thank you.'

And Mrs Dalloway sat down on the sofa with the dress on her knees. All was quiet as she sat sewing the ends of green cloth together, the only sound being a dog heard somewhere far away,.

'Oh dear, there's someone at the front door,' she said, stopping her work. Wide awake, she listened.

'Mrs Dalloway will see me,' a man's voice said downstairs. 'Oh yes, she will see me,' the man said, moving past Lucy, running quickly upstairs, saying to himself now: 'After five years in India, Clarissa will see me.'

'Who can - what can - ?' asked Mrs Dalloway, surprised and not very pleased to have a visitor on the morning of the day that she was giving a party. She heard a hand on the door. She tried to hide her dress but now the door opened and. in came - for just one second she couldn't remember his name, she was so surprised to see him, so happy, so unsure of herself; to see Peter Walsh come to visit her without warning in the morning! (His letter was not yet read.)

'And how are you?' said Peter Walsh, his voice shaking, taking and kissing both her hands. She's grown older, he thought, sitting down. I shan't say anything about it but she's older. She's looking at me, he thought, suddenly feeling uneasy. Putting his hand in his pocket, he took out a large pocket-knife and opened it halfway.

He's just the same, thought Clarissa, the same strange look, the same suit with little squares. His face a little thinner, drier perhaps, but he looks very well and just the same.

'How wonderful it is to see you again!' she said with feeling. He sat with his knife in his hands. That's so like him, she thought.

'I arrived only last night,' he said, 'and I have to go to the country immediately. And how is everything? How is every-body - Richard? Elizabeth? And what's this?' he said, pointing with his knife at the green dress.

He's very well dressed, thought Clarissa, but still he always criticizes me.

Here she is, mending her dress as usual, he thought. She's been sitting here all the time that I've been in India; mending her dress; playing about, going to parties and all that, he thought, feeling more and more angry. There's nothing worse for some women than getting married; and getting mixed up in politics, with a husband like Richard. So it is, so it is, he thought, shutting his knife roughly.

'Richard's very well. Richard's at a meeting,' said Clarissa. And she asked him, taking up her sewing: 'Will you just wait until I finish my dress? We have a party tonight. And I'm not asking you to come, my dear Peter!'

But he loved to hear her say that — 'my dear Peter!' In fact he loved everything: the silver, the chairs.

'Why won't you ask me to your party?' he asked.

Now of course, thought Clarissa, he's so lovable. Perfectly lovable. Now I remember how impossible it was for me to decide — and why did I decide not to marry him, that terrible summer?

'But it's so wonderful that you've come this morning!' she said, putting her hands down one on top of the other on her dress. 'Do you remember,' she said, 'those summer mornings at Bourton?'

'I do,' he said. And he remembered having breakfast alone with her father and feeling very uncomfortable. When her father died, I did not write to Clarissa, he thought.

'I found it difficult to talk to your father,' he said. 'Why didn't I try harder?'

'But he never liked anyone who — any of our friends,' said Clarissa; and immediately was sorry that she said it, not wanting Peter to remember how he asked her to marry him.

And of course I wanted to, thought Peter. It almost broke my heart too, he thought, and that old sadness suddenly grew inside him, climbing up like a moon, both terrible and beautiful, at the end of the day. It was the unhappiest time in my life, he thought. And remembering it all so clearly, he moved a little towards her, put his hand out; let it fall; remembering how he sat with Clarissa in the moonlight.

'Herbert has Bourton now,' she said. 'I never go there now.'

But Peter, now as then, said nothing. Why go back like this to the past, he thought, why does she bring it up again? She hurt me so much at the time. Why?

'Do you remember the lake?' she said, feeling her heart hurting with the sadness, making it difficult for her to speak. And she saw herself standing between her parents by the lakeside, with her life in her arms, then putting it down in front of them and saying: 'This is what I have done with it. This.' And what have I done with it? she thought. A good question, as I sit here sewing this morning with Peter. She felt tears in her eyes.

'Yes,' said Peter. 'Yes, yes, yes.' Stop, he wanted to shout. Because I am not old, he thought, I am only just past fifty. Shall I tell her about Daisy or not? Daisy seems ordinary next to Clarissa. She will think I have wasted my life, he thought, and, yes, in their eyes, in the Dalloways' eyes, I have wasted it. Look at all this: the glass, the silver, the old pictures. In those ways, I have not been a success. And this is Clarissa's life, week after week, married to Richard. While I — and he remembered journeys, rides, quarrels, adventures, card games, falling in love; and work, work, work! He took out his knife and pressed it deep in his hand.

Why does he always play with that knife? Clarissa thought. He always makes me feel shallow, useless, all talk. But I too have work, she thought, picking up her sewing, and she called to her mind the things she did, things she liked; her husband; Elizabeth; herself- all those parts of her life which Peter really didn't know about now — and she began to feel safer.

'Well, and what's happened to you?' she said. So Peter and Clarissa sat face to face on the blue sofa, ready for war. He too now listed all sorts of things in his. mind: his studies at Oxford; his married life, which she knew nothing about; his job, which he did very well.

'Millions of things!' he said loudly, his hands moving up to his head.

Clarissa sat very straight, waiting. 'I am in love,' he said, not to her but to someone pictured in his mind. 'In love,' he repeated rather coldly to Clarissa, 'in love with a girl in India.' There! I have told her my secret. She Gan think what she likes.

'In love!' she said. Caught at his age, with his thin neck, his red hands! And he's six rponths older than I am, she told herself. But in her heart she felt: after all, he has that; he is in love. But not with her. With some younger woman, of course.

'And who is she?' she asked.

'A married woman, unluckily,' he said. 'The wife of a soldier in India.' And he gave a sad little smile. 'She has two small children,' he went on, 'a boy and a girl. And I have come over to plan the divorce.'

Clarissa saw this woman immediately in her mind. She has truly caught him, she thought. What a waste! All his life Peter kept making mistakes like that. How lucky that she didn't agree to marry him! Still, he was in love; her old friend, her dear Peter, in love.

'But what are you going to do? ' she asked.

Oh, the lawyers were going to do it all, he told her. And he began playing with his pocket-knife again.

Oh, leave your knife alone, she wanted to shout. He was never able to understand what other people were feeling. It made her angry. At his age, it was so stupid!

I know what they are all thinking, Peter said to himself, Clarissa and Dalloway and the rest of them. But I'll show Clarissa! And then, to his great surprise, he started to cry. He sat there on the sofa, the tears running down his face. And Clarissa moved forward, took his hand, held him to her, kissed him. And suddenly she felt that the war between them was over, she felt almost light-hearted and happy. Suddenly she realised that happiness was to be with Peter.

It was all over for her: the little room, the narrow bed, the door shut behind her. She called out: Richard, Richard! in her mind. But he is having lunch with Lady Bruton, she remembered. He has left me; I am alone for ever, she thought, putting her hands on her knee.

Peter Walsh got up and crossed to the window, standing with his back to her, a handkerchief in his hand. He looked so deeply unhappy, blowing his nose loudly. Take me with you, Clarissa thought, seeing him at the start of a great journey; and then, a moment later, it seemed that she was at the end of a long, exciting, heart-breaking play, a lifetime lived with Peter; she knew that it was all over.

Now it was time to move and, like a woman at the theatre picking up her things when the play is over, ready to go into the street, she got up from the sofa and went to Peter. And it was terrible and strange, he thought, how, as she came across the room, she was still able to make that sad moon shine out again at Bourton in the summer sky.

'Tell me,' he said, holding her by the shoulders, 'are you happy, Clarissa? Does Richard -'

The door opened.

'Here is my Elizabeth,' said Clarissa proudly. 'How do you do?' said Elizabeth, coming forward. The music of Big Ben noisily sounding the half hour came between them.

'Hullo, Elizabeth,' said Peter, putting his handkerchief away, going quickly to her, saying 'Goodbye, Clarissa' with-out looking at her, leaving the room and running downstairs and opening the front door.

'Peter! Peter!' called Clarissa, following him to the top of the stairs. 'My party tonight! Remember my party tonight!' Her voice seemed thin and very far away as Peter Walsh shut the door.

♦

Remember my party, remember my party, said Peter Walsh, walking down the street. Clarissa's parties. Why does she give these parties? he thought. But only one person in the world was what he was — in love for the first time in his life. He looked at himself in the window of a shop selling cars. Clarissa has grown hard, he thought, looking with interest at the fine cars in the window; he understood machines. The way that she said: 'Here is my Elizabeth' — he did not like that. Why not just 'Here's Elizabeth*? And Elizabeth didn't like it either. There was always something cold about Clarissa, he thought. Was she angry because of his calling at that hour in the morning? Suddenly he felt sorry that he cried just now; showed his feelings; told her everything, as usual.

Nobody knew he was in London, only Clarissa. He felt that he was on an island: the strangeness of standing alone, alive, unknown, at half-past eleven in Trafalgar Square. Why do I do it? he thought. The divorce suddenly seemed a waste of time. Instead he felt full of understanding, kindness and unusual happiness. I haven't felt so young for years, he thought, and so free - like a child that has run away from home.

Now look at that lovely young woman, he thought, seeing a girl pass in front of him. She's perfect. Young. Not married. Not proud, like Clarissa; not rich, like Clarissa; amusing, probably; calm. She moved on. He started to follow her. If she stops, I shall speak to her, he thought. But other people got between them in the street. He nearly lost her. On and on she went in front of him and now the moment was coming, she walked more slowly, opened her bag, took out a key, looked his way — but not at him. Then she opened a door and was gone! Clarissa's voice calling: 'Remember my party, remember my party' sang in his ears. His adventure was over.

His excitement was over, it was broken in pieces. Well, I've had my fun, he thought. He walked on, planning to find somewhere to sit until it was time to go to the lawyers and talk about the divorce. But where to go? It didn't matter. Up the street then, towards Regent's Park, since it was still very early. I shall sit down somewhere out of the sun, he thought, and have a smoke. There was Regent's Park. He remembered coming here as a child: the long straight walk. He looked for a place to sit, feeling now a little sleepy. She's a strange- looking girl, he thought, remembering Elizabeth as she came into the room and stood by her mother. Quite grown up, more handsome than pretty; and she's not more than eighteen. She probably doesn't feel comfortable with Clarissa. 'Here's my Elizabeth' — trying to show, like most mothers, that things are what they're not. She tries too hard. She goes too far.

Sitting in the park, he drew in the rich smoke of his cigar and sent it out again in rings: blue circles, which kept their shape in the air for a moment, then blew away. I shall try to get a word with Elizabeth tonight, he thought. Suddenly he closed his eyes and with a tired hand threw away the end of his cigar. A strong wind seemed to blow across his mind, leaving it empty of dancing leaves, children's voices, people passing, the sound of traffic now near, now far. Down, down he dropped, into the soft bed of sleep.

♦

He woke suddenly, saying to himself, 'The heart is dead.' The words were part of some picture, some room, some time in the past, seen in his sleep. Slowly the picture grew clearer. It was at Bourton, that summer early in the nineties, when he was so deeply in love with Clarissa. There was a room full of people sitting round a table after tea and the light was yellow and heavy with cigarette smoke. They were laughing about a neighbour. Clarissa's friend Sally said suddenly: 'Did you know that woman had a baby before she got married?' Clarissa's face went pink and she said: 'Oh, I shall never be able to speak to her again.' How he disliked her at that moment! She was hard, proud, unsure of herself. 'The heart is dead.' It was her heart that was dead. Sally Seton was Clarissa's greatest friend in those days: dark, good-looking, amusing, always getting into trouble. Clarissa's old father disliked both her and him, which brought them closer to-gether.

Then Clarissa, seeming to be angry with them all, got up and went off by herself. As she opened the door, that big hairy dog came in, the one that ran after sheep. She threw her arms round it; but the message meant for Peter was: 'I know you didn't like what I said about that woman: but just see how I love my dog!' They were always able to speak to each other silently, without using words: this game with the dog was an example of that. She knew that he was criticizing her. And he always knew just what she was doing. He didn't say anything of course. He just sat there woodenly. She shut the door. He remembered feeling terribly sad. It all seemed useless - this being in love; having quarrels; trying to be friends again. He walked off alone, feeling sadder and sadder. He couldn't see her, couldn't explain to her. There were always other people about. That was the trouble with her — something cold, something stony in her, some part of her that he could never get through to. It was the same problem when he was talking to her this morning. But he still loved her. The thought of her gave him no rest.

That terrible evening he sat without speaking, just eating. And halfway through the meal he looked across at Clarissa for the first time. She was talking to a young man on her right. Suddenly he saw the truth. 'She will marry that man,' he said to himself. He didn't yet know his name. He was a fair-haired young man, looking a little uncomfortable, who said to everyone: 'My name is Dalloway.' That was the beginning of it all. He felt so hurt, so alone. He heard them talk about coats, that it was cold on the water and so on. The others were taking a boat out on the lake in the moonlight - one of Sally's wild ideas. They left. He was quite alone. And he turned round and suddenly there was Clarissa, come back to get him. He realized then her thoughtfulness, her kindness.

It was the happiest moment of his life. Without a word they were friends again. They walked down to the lake together. He had twenty minutes of perfect happiness. He remembered her voice, her laugh, her white dress... And all this time he knew that Dalloway was falling in love with her. But it didn't seem to matter. And then in a moment it was over. Getting into the boat, he said to himself: 'Dalloway will marry Clarissa.'

The final part of the story happened at three o'clock in the afternoon on a very hot day. He sent a message to her by Sally to meet him in a corner of the garden. She came, before the time in fact. They stood there with the plants between them. 'Tell me the truth,' he kept saying. She did not move. 'Tell me the truth,' he repeated. She was as hard as metal, as a stone. He spoke for hours, his tears falling continuously. And when she said: 'It's no good, it's no good. This is the end,' it was as bad as being hit in the face. She turned, she left him, she went away.

'Clarissa!' he shouted. 'Clarissa!' But she never came back. It was over. He went away that night. He never saw her again.

♦

It was terrible, he thought, terrible! Still, the sun was hot. All things pass with time. He looked around him at Regent's Park, not much changed since he was a boy. London was looking wonderful, he thought, getting up and walking across the grass: the softness of the colours; the richness; the greenness after India. He remembered Sally Seton: the wild Sally. She was probably the best of all Clarissa's friends. Now she was married to a rich man and lived in a large house near Manchester. And there was Dalloway — not very clever but honest and likeable; not much good at politics. He was best with animals, dogs and horses, living in the country. And Clarissa thought so highly of him.

together. He had twenty minutes of perfect happiness. He remembered her voice, her laugh, her white dress .. . And all this time he knew that Dalloway was falling in love with her. But it didn't seem to matter. And then in a moment it was over. Getting into the boat, he said to himself: 'Dalloway will marry Clarissa.'

The final part of the story happened at three o'clock in the afternoon on a very hot day. He sent a message to her by Sally to meet him in a comer of the garden. She came, before the time in fact. They stood there with the plants between them. 'Tell me the truth,' he kept saying. She did not move. 'Tell me the truth,' he repeated. She was as hard as metal, as a stone. He spoke for hours, his tears falling continuously. And when she said: 'It's no good, it's no good. This is the end,' it was as bad as being hit in the face. She turned, she left him, she went away.

'Clarissa!' he shouted. 'Clarissa!' But she never came back. It was over. He went away that night. He never saw her again.

♦

It was terrible, he thought, terrible! Still, the sun was hot. All things pass with time. He looked around him at Regent's Park, not much changed since he was a boy. London was looking wonderful, he thought, getting up and walking across the grass: the softness of the colours; the richness; the greenness after India. He remembered Sally Seton: the wild Sally. She was probably the best of all Clarissa's friends. Now she was married to a rich man and lived in a large house near Manchester. And there was Dalloway - not very clever but honest and likeable; not much good at politics. He was best with animals, dogs and horses, living in the country. And Clarissa thought so highly of him.

♦

No, No! He was not in love with her any more. He only knew, after seeing her this morning at her sewing, getting ready for the party, that he couldn't stop thinking about her. It was not being in love, of course. It was thinking about her, criticizing her, starting again after thirty years trying to explain her. She liked people who were successful, who got on in the world - he remembered her telling him that. She brought people to her, she made her sitting-room a kind of meeting place. And spent her time visiting people, running about with bunches of flowers and little presents. But she did these things honestly, her kindness was natural. She believed in doing good. And of course she enjoyed life so much. It was natural for her to enjoy things. But she needed people around her and so she wasted time with lunches and dinners and talk. And she gave great importance to Elizabeth, with her round eyes and whitish face, not in any way like her mother; who listened calmly to her mother and then said: 'Can I go now?' like a child of four.

The truth about growing older, he thought, coming out of the park, is that one doesn't really need people any more. Life itself, every moment of it, here, now, in the sun, in Regent's Park — life itself is enough. Too much, in fact. It takes a lifetime to enjoy everything fully, to understand every mean-ing. Life cannot hurt me again the way that Clarissa hurt me, he thought. For hours at a time he never thought of Daisy.

So did he really love Daisy then, with the same sort of love that he felt in the old days? No, it was quite different; because this time she was in love with him. And perhaps that was why he felt almost happy when the ship finally sailed. He just wanted to be alone. If we're honest, we know that we don't want people after fifty, we don't want to go on telling women that they're pretty. That's what most men of fifty feel, thought Peter Walsh.

So why did he suddenly start crying this morning? What was all that about? What did Clarissa think of him? - that he was just stupid probably, and not for the first time. It was jealousy that was behind it, the feeling that lives longer in our hearts than any other, Peter Walsh thought, holding out his pocket-knife in front of him. Daisy wanted him to feel jealous: in her last letter she told him about meeting Major Orde. It made him so angry. He didn't want Daisy to marry some other man. And when he saw Clarissa, so calm, so cold, so interested in mending her dress, he realized that she brought out those feehngs, made him look a stupid, tearful old man. Women don't know what we men feel, he thought, how strong men's feelings are. Clarissa is as cold as ice. She sits there beside me on the sofa, lets me take her hand, then gives me a cold little kiss.

It was time to cross the road. He crossed and then took a taxi.

♦

His lunch with Lady Bruton was over. Richard was walking back to Westminster. 'Peter Walsh is back in London,' Lady Bruton was telling them at lunch. Then they talked of that rime when Peter was so much in love with Clarissa. Suddenly Richard wanted to be with his wife, to tell her openly in words that he loved her; usually it was a subject that they never spoke of. But he wanted to come in holding something. Flowers? So he bought a big bunch of red and white roses. It's a great mistake not to say it, he thought, as a time comes when you can't say it any more. He wanted to hold out his flowers to her and say: 'I love you.' Marrying Clarissa was the greatest piece of luck, he thought, as he walked across Green Park. Long ago he felt jealous because of Clarissa and Peter Walsh. But she says she was right not to marry him;

So why did he suddenly start crying this morning? What was all that about? What did Clarissa think of him? - that he was just stupid probably, and not for the first time. It was jealousy that was behind it, the feeling that lives longer in our hearts than any other, Peter Walsh thought, holding out his pocket-knife in front of him. Daisy wanted him to feel jealous: in her last letter she told him about meeting Major Orde. It made him so angry. He didn't want Daisy to marry some other man. And when he saw Clarissa, so calm, so cold, so interested in mending her dress, he realized that she brought out those feelings, made him look a stupid, tearful old man. Women don't know what we men feel, he thought, how strong men's feelings are. Clarissa is as cold as ice. She sits there beside me on the sofa, lets me take her hand, then gives me a cold little kiss.

It was time to cross the road. He crossed and then took a taxi.

♦

His lunch with Lady Bruton was over. Richard was walking back to Westminster. 'Peter Walsh is back in London,' Lady Bruton was telling them at lunch. Then they talked of that time when Peter was so much in love with Clarissa. Suddenly Richard wanted to be with his wife, to tell her openly in words that he loved her; usually it was a subject that they never spoke of. But he wanted to come in holding something. Flowers? So he bought a big bunch of red and white roses. It's a great mistake not to say it, he thought, as a time comes when you can't say it any more. He wanted to hold out his flowers to her and say: 'I love you.' Marrying Clarissa was the greatest piece of luck, he thought, as he walked across Green Park. Long ago he felt jealous because of Clarissa and Peter Walsh. But she says she was right not to marry him;

and clearly that is true. Happiness is this, he thought, entering Dean's Yard as Big Ben began to sound the hour.

In her sitting-room, Clarissa sat at her writing table, feeling far from pleased. It's true that I haven't asked Ellie Henderson to my party. Now Mrs Marsham writes: 'Ellie so much wants to come.' But why must I ask all the boring women in London to my parties? she thought. She too heard the sound of the clock: One . . . two . . . three. Three already! But at that moment the door opened and in came Richard. What a surprise! He was holding out flowers — roses, red and white. (But he could not bring himself to say that he loved her — not using real words.)

'But how lovely!' she said, taking his flowers. She under-stood: his Clarissa. She put them in water. 'How lovely they look!' she said. And was the lunch enjoyable? she asked. Did Lady Bruton ask about her? 'Peter Walsh is back. Mrs Mar- sham wants me to ask Elbe Henderson. That Kilman woman is upstairs with Elizabeth.'

'But let us sit down for five minutes,' said Richard. All the chairs were against the walls. Oh yes, it was for the party.

'Peter Walsh is back. He came round this morning. He's going to get a divorce. And he's in love with some woman in India. He hasn't changed a bit.'

'We were talking about him at lunch,' said Richard. (But he still could not tell her that he loved her. He held her hand. Happiness is this, he thought.) 'And our dear Miss Kilman?' he asked.

'She arrived just after lunch and she and Elizabeth are together upstairs, studying heavy books, probably. She came with her raincoat and umbrella,' - said Clarissa. 'And why must I ask that boring Ellie Henderson to my party?'

'Poor Ellie Henderson,' said Richard. She takes her parties so seriously, he thought. 'I must go,' he said, getting up. But first he made her he down. 'You need a full hour's rest after lunch,' he said. This was what the doctor once told her. Now Richard always said it. He was so lovable, so kind; he just went and did things instead of talking about them. He went off to his meeting at the House of Commons.

I will lie down then, she thought, as he wants me to. But — why did she suddenly feel this deep unhappiness? It was not because of Richard or Elizabeth. It was something unpleasant from earlier in the day, something that Peter said, together with her feelings of hopelessness up in the bedroom, taking off her hat. Her parties! That was it! Her parties! Peter believed that she liked mixing with famous people, great names. Richard just thought her silly to like excitement, when she knew it was bad for her heart. And both were quite wrong. What she liked was just living.

'That's what I do it for,' she said, speaking to life. Lying on the sofa, she could hear the noises from the street, feel warm air blowing in through the windows. But your parties — why do you give your parties? she could hear Peter 'saying. Why are they so important? They're a kind of giving, she told herself. A way of giving thanks. Helping people, bringing them together from all over London, from Kensington and Mayfair. It's the only important thing I know how to do. I can't write or paint or sing very well. I'm not very intelligent. But one day follows another; to wake up in the morning; to see the sky; to walk in the park; to meet someone I know, like Peter; to get a bunch of roses. This is enough, and being dead is so unbelievable: that it must all end; and no one in the world will know how much I have loved it all, every moment.

♦

The door opened. Elizabeth knew that her mother was resting. She came in very quietly. She stood perfectly still. Not looking like one of the Dalloways, who had fair hair and blue eyes. Elizabeth instead was dark, with Chinese eyes in a white face; pleasant, thoughtful, calm. As a child, full of laughter, but now at seventeen, very serious. She stood quite still and looked at her mother; but Miss Kilman, full of jealousy, was just outside the door, listening to what they said. Mrs Dallo-way came out with her daughter. Elizabeth knew that Miss Kilman and her mother had a deep dislike for each other. She felt uncomfortable to see them together. She ran upstairs to find her hat.

'You are taking Elizabeth to the shops?' Mrs Dalloway said. Miss Kilman said that she was. Miss Kilman was not going to make herself pleasant: she worked verfy hard, she studied; while this other woman did nothing, believed in nothing; just looked after her daughter. And here was Eliza-beth back again, the beautiful girl. Laughing, Clarissa said goodbye. Downstairs they went together, Miss Kilman and Elizabeth. Secretly hurt that this woman was taking her daughter from her, Clarissa called out after them: 'Remember the party! Remember our party tonight!' But already the front door was open and Elizabeth did not answer. Now that Miss Kilman was gone, the idea of her came back to Clarissa more strongly: narrow, jealous, hard;- always so sure that she was right. A deeply dislikeable woman. But Big Ben was sounding the half hour and Clarissa remembered all sorts of little things — Mrs Marsham, Ellie Henderson, glasses for ices. She must telephone immediately.

♦

Peter Walsh, feeling tired and hot, stood by the letter-box opposite the British Museum, heard the sound of an ambu-lance high and loud above the traffic noise and thought about living and dying. And thought still about Clarissa, sitting with her once on the top of a bus. Over the years she came to his mind like this in all sorts of places: on a ship; in the Himalayas; picturing her most often in the' country, not in London. Remembering her at Bourton . . .

He arrived at his hotel and took the key. The young woman at the desk gave him some letters. As he went upstairs, he thought of Clarissa at Bourton, when he stayed there for a week or two in late summer. He pictured her on top of a hill, her coat blowing out in the wind, pointing to the river below. Or under the trees, trying to cook something on a fire, with smoke blowing in their faces. Or walking together for miles across the country while the others drove, talking all the time about people, about politics, so that he never noticed a thing until she pointed it out to him. Clarissa walking in front of him across the fields with a flower for her aunt, walking on and on without ever getting tired.

Oh, it was a letter from her - this blue envelope in her handwriting. He didn't want to read it but he must. It is sure to hurt me, he thought.

'"How wonderful it was to see you. I must tell you that.'" That was all.

It made him uncomfortable, almost angry. Why did she write it? Couldn't she leave him alone? She and Dalloway were married now, living in perfect happiness all these years. His hotel room now seemed empty, unwelcoming: a bed, a chair, a glass. His books, letters, clothes did not seem to belong here. It was Clarissa's letter that made him see all this. Wonderful to see you.' Why did she have to say it? He pushed the letter away; he never wanted to read it again.

The letter was here by six o'clock. That means that she sat down to write it immediately after he left her. So she felt sorry for him, wanted to please him, wanted him to find that one line waiting: 'Wonderful to see you'. And she meant it.

He emptied his pockets. Out came his pocket-knife and a photograph of Daisy, all in white with a dog sitting on her knee. And she was twenty-four and had two children. Here he was, at his age, in real trouble. And if they did marry? It was all right for him but what about her? Giving up her children, living on when he was dead. Well, she must decide for herself, he thought, walking around in his socks, taking out a clean shirt. Perhaps I will go to Clarissa's party, he thought, or to the theatre; or perhaps stay in and read a book. Perhaps his life with Daisy was not to be. He picked up his watch, his money, his knife, Daisy's photograph, Clarissa's letter. And now for dinner.

♦

It was going to be a very hot night. Peter Walsh sat in a chair outside the hotel after dinner, as the day changed to evening like a woman changing her dress. The traffic was now lighter. Lights shone here and there among the thick-leaved trees in the squares. He bought an evening paper to read the sports page. Then, leaving it on the table and taking up his hat and coat, he started out for the party.

This was her street, Clarissa's. His mind must come alive now, his body must awake, entering the house, the lighted house where the door stood open, where cars were stopping with bright women getting out of them. The heart must now

be brave. He opened his pocket-knife.

♦

Lucy came running downstairs and stopped for a moment to look at the rooms, so clean and bright and shining. Then, hearing voices from below, she ran on. Mrs Dalloway wanted her to bring up the wine. Miss Elizabeth looked quite lovely in her pink dress, she told the cook. Someone had to shut up Miss Elizabeth's dog, because it bit people.

Mr Wilkins (paid specially to do this) was calling out the names of people arriving: Lady and Miss Lovejoy ... Sir John and Lady Needham . . . Miss Weld . . . Mr Walsh.

'How wonderful to see you!' said Clarissa. She said it to everyone. It was not honest — Clarissa at her worst. It was a mistake to have come: much better to stay at home and read a book, thought Peter Walsh. He knew no one.

Oh dear, the party was not going to be a success, it was all quite hopeless, thought Clarissa, as she stood listening to old Lord Lexham. Why did she do these things? She could see Peter out of the corner of her eye, standing there criticizing. Why did he come then, just to criticize? He was walking away, she must speak to him. But old Lord Lexham was talking to her. There was Ellie Henderson, asked at the last moment. Ah, Richard was welcoming her. 'Many people really feel the hot weather more than the cold,' she was saying.

'Yes, they do,' said Richard Dalloway. 'Yes.'

'Hullo, Richard,' said somebody, taking him by the arm. And there was old Peter, old Peter Walsh, not changed a bit. He was so happy to see him — so very pleased to see him. They went off together across the room.

Clarissa saw the crowd of people all talking, drinking, laughing. It's going to be all right now, my party, she thought. It has started. It has begun. More and more people were arriving. She had six or seven words with each of them and they went on into the rooms. And yet she was not enjoying it. Every time she gave a party, she had this feeling of not being herself, that everyone was unreal in one way and much more real in another. People forgot their ordinary ways, said things they never said at other times.

'How wonderful to see you,' she said. Dear old Sir Harry! 'Of course you know everyone.' What was that name? Lady Rosseter. Who then was Lady Rosseter?

'Clarissa!' That voice! It was Sally Seton. Sally Seton after all these years. But she never looked like that, all those years ago. To think of her under this roof, under this roof. Words and laughter flew - 'passing through London, heard about your party, had to see you!'

Yes, it was so surprising to see her again: older, happier, no longer lovely. They kissed each other, first this side, then that, and Clarissa turned with Sally's hand in hers and saw the rooms full, loud with voices, saw the silver, the roses given by Richard.

'I have five big boys,' said Sally. 'I can't believe it!' said Clarissa, full of happiness as she remembered the old days. But someone wanted her. The Prime Minister was here. No one was looking at him, they all went on talking, but it was clear that they all knew he was there. Clarissa took him down the room in her silver-green dress.

'Dear Clarissa,' said old Mrs Hilberry. 'Tonight you look so like your mother when I first saw her, walking in a garden in a grey hat.' Clarissa's eyes swam with tears. Her mother walking in a garden! But she must move on. There was the Professor. There was old Aunt Helena with her sdck. Where has Peter Walsh gone? she thought. Ah, there he was. 'Come and talk to Aunt Helena about Burma,' said Clarissa.

And I still haven't had a word with her all evening, Peter thought. 'We will talk later,' said Clarissa, taking him up to Aunt Helena. 'Peter Walsh,' said Clarissa. 'He has been in Burma.'

Now she must speak to Lady Bruton. 'Richard so enjoyed his lunch party,' she said. 'And there's Peter Walsh!' said Lady Bruton, who could never think of anything to say to Clarissa. She shook hands with Peter. She asked "him to come to lunch.

Was that Lady Bruton? Was that Peter Walsh grown grey? Sally Seton (now Lady Rosseter) asked herself. And Clarissa! Oh Clarissa! Sally caught her by the arm.

'But I can't stay,' she said. 'I shall come later. Wait. I shall come back,' she said, looking at her old friends Sally and Peter, who were shaking hands and laughing. But Sally's voice no longer had its beautiful richness, her eyes didn't shine as before, when she ran out of the bathroom with no clothes on. Sally, who loved excitement, danger, always at the centre of things, Sally who was sure to die young, Clarissa thought then. And instead she was married to a rich man with no hair and lived in Manchester. And she had five boys!

Sally and Peter were sitting together talking about old times - the garden at Bourton; the sitting-room wallpaper; the old man who sang without any voice. Times we three all spent together, she thought. A part of this Sally must always be and Peter must always be. But she must leave them and talk to the Bradshaws, who she did not like.

At last she went into the little side-room where earlier the Prime Minister was sitting. Now there was nobody. The noise and brightness of the party died away. It was strange suddenly to be alone here in her party dress. Just now the Bradshaws were talking of a young man who killed himself today. Once she remembered throwing away a sixpence. But this boy has thrown away his life! And we go on and we grow old, thinking of Peter, of Sally. Loving and dying. Deep in her heart she felt again what she felt this morning: the darkness, that black darkness. So far, I have escaped; but that young man killed himself. So here and there people disappear and I am left standing in my evening dress. She walked to the window and watched in the house opposite an old woman going to bed alone. The clock began to tell the hour: one, two, three. The old woman put out her light. But look at the time! She must go back. She must find Sally and Peter. And she came in from the little room.

♦

'But where is Clarissa?' said Peter, sitting on the sofa with Sally. 'Where has she gone?'

'There are important people that she has to be nice to,' said Sally. 'I have five sons,' she told him.

How she has changed, thought Peter. He remembered his tears the night he left Bourton, and Sally waiting with him until he caught the train.

He still plays with his knife, thought Sally, opening and shutting it every time he gets excited. Once they were so close, she and Peter Walsh, that summer when he was in love with Clarissa. But she didn't often see Clarissa now? Peter went off to India, she heard he was unhappily married, she didn't want to ask if he had any children. He looked older but also kinder, she thought.

'Have you written any books?' she asked. 'Not a word,' said Peter Walsh and she laughed. She was still pleasing, still a real person, Sally Seton.

'Yes,' said Sally laughing, 'I have a great big house and ten thousand pounds a year. You must meet my husband. You will like him.' And this was Sally who once had nothing, who had to sell some of her rings because she wanted to come to Bourton.

'And that's Elizabeth over there. She's not a bit like Clar-issa,' Peter Walsh said.

'Oh Clarissa,' said Sally. 'We were great friends,' she told Peter, 'but something was wrong. She is lovely, Clarissa was always lovely; but why did she do it, Peter? Why marry Richard Dalloway who is only interested in dogs and horses? And then,' she waved her hand at the room, 'all this. Have you got any children?'

'No,' Peter told her. 'No sons, no daughters, no wife.'

'But you look younger than any of us,' said Sally.

'It was a silly thing to do,' Peter said, 'to get married like that. But we had a wonderful time.'

What does he mean? thought Sally. At his age he must surely feel alone, with no home, nowhere to go. 'You must come and stay with us,' she said, 'for weeks and weeks.' And then the truth came out. 'The Dalloways have never once come to see us. We asked them so many times but Clarissa will not come. She thinks that I married below me. My husband is a workman's son.' That, she knew, was the problem.

Was Clarissa really like that? thought Peter. Yes, probably. Where was she all this time? It was getting late.

'But,' said Sally, 'when I heard that Clarissa was giving a party, I felt that I had to come - I had to see her again. So I just came. It's so important, isn't it, to say what you feel.'

'But I do not know what I feel,' said Peter Walsh.

Poor Peter, thought Sally. Why didn't Clarissa come and talk to them? That was what he really wanted. All this time he was thinking only of Clarissa and playing with his knife.

'My life hasn't been easy,' Peter said. 'And my feelings for Clarissa have not been easy to understand. It has been a great problem in my life. You can't be in love twice.'

What could she say? It's better to have loved - he must come and stay with them in Manchester. 'You mean more to Clarissa than Richard ever did. I'm sure about that,' said Sally.

'No, no, no!' said Peter. Sally went too far. Richard was a very good person - there he was at the end of the room, the same as ever, dear old Richard.

'But what has he done in life?' Sally asked. 'And are they happy together? Really, I know nothing about them. What can one know about other people?' she said.

But Peter did not agree. 'We know everything,' he said. 'Anyway, I feel that I do.'

'There's Elizabeth,' he said. 'She feels not half of what we feel, not yet.'

'But,' said Sally, watching Elizabeth go to her father, 'you can see that they really love each other.'

Father and daughter stood together now that the party was almost over. The .rooms were getting emptier and emptier, with things lying on the floor. Ellie Henderson was finally going. Richard and Elizabeth felt rather glad that it was over but Richard was proud of his daughter. He had to tell her that. How he looked at her and thought: who is that lovely girl? And it was his daughter!

'I must go and talk to Richard,' said Sally. 'I shall say goodnight. It's not the mind that matters, Peter, it's the heart.'

'I will come,' said Peter; but he sat there for a moment. What is this feeling that hurts me so? What is this happiness? he thought to himself. What is this great excitement that burns inside me?

'It is Clarissa,' he said.

And there she was.

THE PLACES IN THE STORY

Mrs Dalloway lives in the centre of London, in Westminster near Dean's Yard. Her house is not far from Big Ben, the famous clock of the Houses of Parliament, where her husband Richard works. To buy her flowers in Bond Street, she crosses first Saint James's Park and then Piccadilly.

When Peter Walsh leaves Clarissa's house, he walks to Trafalgar Square and from there he goes north to Regent's Park, where he has a rest. His hotel is near the British Museum and in the evening he walks from there back to Clarissa's house in Westminster for the party. Mayfair and Kensington are parts of central London where some of Clar-issa's friends live.

The Dalloway house is like many older houses in London. The kitchen is below the ground, the sitting-room is upstairs on the first floor and the bedrooms are on the floor above.

ABOUT VIRGINIA WOOLF

Virginia Woolf was born in 1882 and spent most of her early life in London. With her sister Vanessa, a well-known painter, she was one of a group of painters and writers known as the Bloomsbury Group. With her husband Leonard, she started the Hogarth Press from her home in Richmond. The Press brought out nearly all her own books and also T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Her best-known books are: Orlando, The Waves and To the Lighthouse. For many years she also wrote every day about her own thoughts, feelings and life: this is the famous Diary of Virginia Woolf She was often ill, and sometimes out of her mind, in hospital for months at a time. In 1941 she finally killed herself by throwing herself into the River Ouse.

People now think of her as one of the greatest British writers of the twentieth century.

EXERCISES

Comprehension

Here are some words spoken by different people in the story. Explain: who speaks the words; who the person is speaking to; where the people are at the time; what is happening in that part of the story.

1. 'She is under this roof!'

2. 'Will you just wait until I finish my dress?'

3. 'I am in love with a girl in India.'

4. 'Tell me the truth! Tell me the truth!'

5. 'It's not the mind that matters, it's the heart.

1. Do you think that Clarissa was right not to marry Peter Walsh? Say why or why not.

2. Peter Walsh often plays with his pocket-knife. Why do you think he does this? What does it tell us about him?

Writing

1. Write one or two sentences about these parts of Mrs Dalloway's house, explaining why they are important in the story:

a) the entrance hall

b) the bedroom

c) the sitting-room.

2. Choose a person in the story. Write three sentences about how he or she looks and three more sentences about what they think and do in this story.

Review

1 Time is very important in this story. Describe the different ways in which the writer uses time. What do you think she is trying to show us about it?

2 What do you think about the story? Do you find it unusual in any way? Say why you like or dislike it.

GLOSSARIES

life 生活

moment 瞬间,片刻

criticizing 批评,非难

hostess 女主人

successful 成功的

alone 孤独的

message 消息,讯息

sex 性

politics 政治

jealous 嫉妒的,妒忌的

quarrels 口角,争吵

sewing 缝制物

mind 记忆,回忆

divorce 离婚

lawyers 律师

tears 眼泪

truth 真相,事实

注:以上所列单词为书中黑体宇

图书在版编目(CIP)数据

黛洛维夫人:英文/(英)伍尔夫著

北京:外文出版社,1996

ISBN 7-119-01819—1

英国企鹅出版集团授权外文出版社 在中国独家出版发行英文版

企鹅文学经典

英语简易读物 (阶梯二)

黛洛维夫人

弗吉尼亚"伍尔夫著

责任编辑:余军

外文出版社出版 (中国北京百万庄路24号)

邮政编码100037

煤炭工业出版社印刷厂印刷

1996年(32开)第一版 (英)

ISBN 7-119-01819 -1/I. 393(外)

著作权合同登记图字01-96-0330 定价:2.80元

https://m.sciencenet.cn/blog-500800-479490.html

上一篇:英文写作圣经—《风格的要素》The Elements of Style

下一篇:英语修辞高峰会——Chapter 2 表示因果关系的句子(by 旋元佑)